The Visionary: Philip K. Dick

All his life Philip K. Dick believed he could see the future. Turns out he was right

During his lifetime Philip K. Dick endured the trials of the struggling writer. There were the missed car payments, the loans from friends to pay looming tax bills. There were collapsed marriages and stints in rehab – results of the ferocious drug consumption, mostly amphetamines that drove his early work. And running through it all was near poverty, and the need to write just to eat. On a few occasions he didn’t write enough, or at least not enough that anyone wanted to buy, and he and his wife subsisted on dog food.

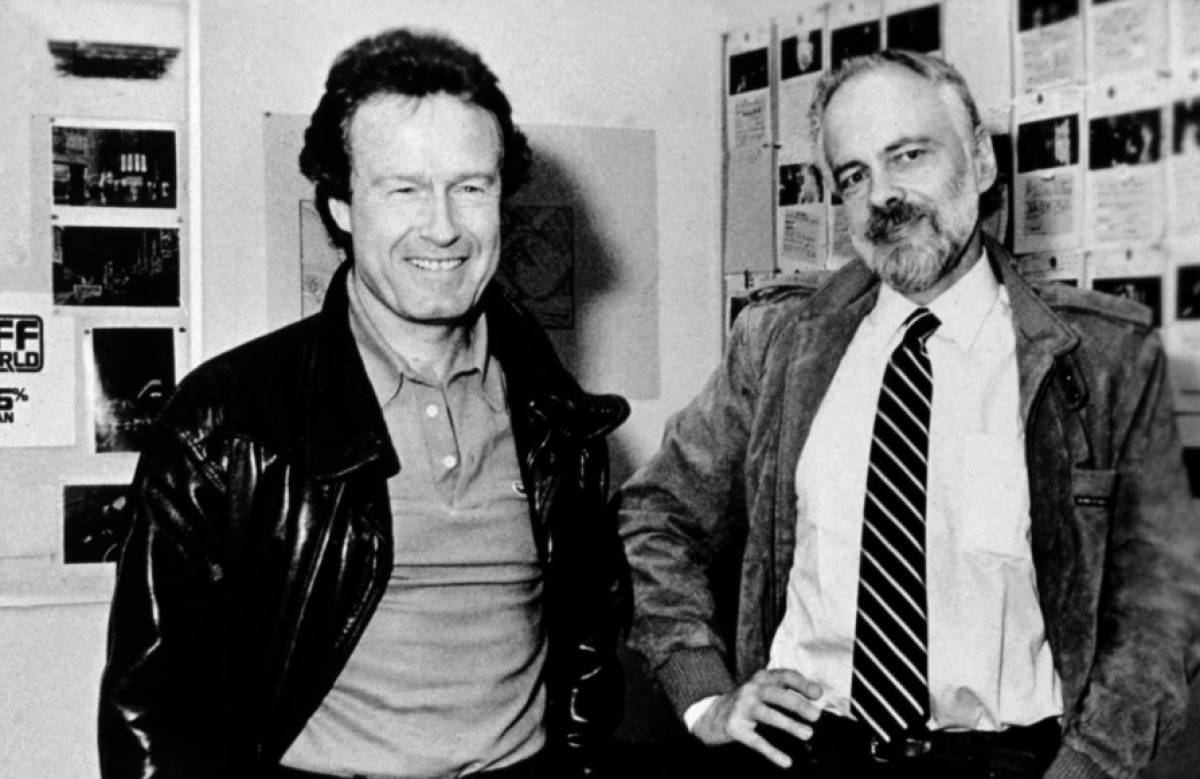

But in the Autumn of 1981 things were finally looking up. In October of that year Jeffrey Walker, a marketing executive at The Ladd Company who had been put in charge of hyping Blade Runner, received a letter from Dick, on whose 1968 novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? Ridley Scott’s movie was based. Dick had been tipped off by a friend that local news network was going to show some early footage of the film and he had watched glimpses of Scott’s fog-shrouded dystopia with increasing excitement.

“The impact of Blade Runner is going to be overwhelming,” an ecstatic Dick had written. “[It] is going to revolutionise our conceptions of what science fiction is, and more, what it can be.”

Six months later, just weeks before Scott’s film was released, he was found unresponsive in his Santa Ana home. Ten days later he died in hospital of a heart attack which had followed a massive stroke. He was 52.

There is something of the cosmic joke about it. At the very moment when the ideas were about to finally get their moment in the spotlight, their author was snatched away. Given Dick’s mordant sense of humour he might even have spared a thin laugh.

Nevertheless Dick was, as it turns out he often would be, right. Blade Runner was a slow burn, its initial release stymied by uncomprehending reviews and misconceived marketing. But almost immediately it began to warp the world around it. With Scott’s film acting as a kind of transmission vector, Phildickain ideas began to infect the mainstream, not just of cinema and written science fiction, which it undoubtedly changed forever, but increasingly in the new anxieties and nightmares that began to permeate the modern age.

In 2020 it’s disconcertingly clear that we are entering a future Dick sketched for us decades ago. After all here was the man who 50 years ago declared: “There will come a time when it isn’t ‘They’re spying on me through my phone’ anymore. Eventually, it will be ‘My phone is spying on me’”

Sound familiar?

Philip Kindred Dick was born just before Christmas in 1926 in the middle of a bitter Chicago winter along with a twin sister, Jane, six weeks premature. He was lucky to survive. His mother, struggled to care for the severely underweight babies. Though she didn’t know it, the two children were in fact slowly starving to death and it was only when Jane’s leg was accidentally scalded with a hot water bottle that a doctor was called. Diagnosing acute malnutrition in both infants and he called an ambulance. Jane died on the way to hospital. Philip had been, the doctors later told her, within a day or so of death.

It was a traumatic beginning and there are those who see in this chaotic entrance the seeds of his later fiction; set in a universe where nothing is certain, where everything you think is permanent, reliable, right next to you can be torn away.

As a teenager living in Berkeley, California – then ground zero for the countercultural youthquake – Dick became obsessed with science fiction but it wasn’t until his early 20s that he himself decided to pursue a career as a writer. Scores of stories were written and rejected before his first sale, Roog, to The Magazine of Fantasy And Science Fiction in 1951. He was paid the princely sum of $75. He would rarely earn all that much more.

He spent the better part of the ’50s and ’60s churning out story after story for his beloved pulps, dozens a year, in the process perfecting both his talent for brilliant, off-kilter titles – Beyond Lies The Wub, Now Wait For Last Year, Flow My Tears The Policeman Said – and refining his enduring themes.

Dick’s stories dealt with a world in which people and machines have overlapped, in some cases becoming indistinguishable from one another, and the corrosive, unexpected effects of these new unrealities on the experience of being human. He was mesmerised by what he felt were the increasingly porous borders between the real and the simulated, and alarmed by the faceless armies that might police them.

“We live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations,” he had written in 1978. “I ask ‘what is real?’ Because increasingly we are bombarded by pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. It is an astonishing power, that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing.”

And so, decades before The Matrix or Inception there was his 1969 novel Ubik (a fantastic starting point for new readers), which had alternate realities created by psychics suspended between life and death. Before The Truman Show there was Time Out Of Joint, Dick’s 1959 novel in which Ragle Gumm begins to suspect that he exists in a world created especially for him.

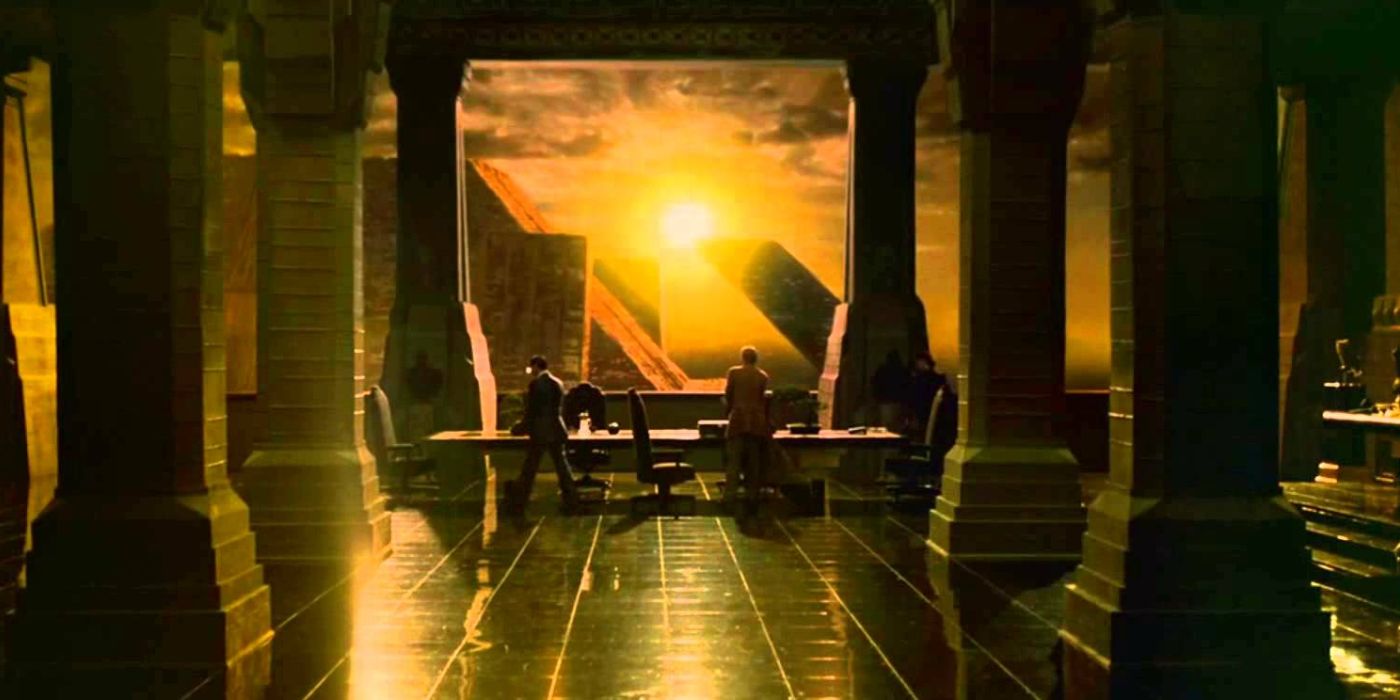

And controlling these borders between the real and the simulated were not nation states or armies, but vast, anonymous corporations. The Tyrell Company of Blade Runner or REKAL of We Can Remember It For You Wholesale (reimagined as an action spectacular by Paul Verhoeven in Total Recall).

For decades Dick’s ideas remained confined to the more exotic fringes of the S.F. scene. Unlike the other big names of the era – Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein – Dick wasn’t interested so much in technology in itself, the spaceships and ray guns, but in the anxieties he foresaw in its relentless encroachment on human life. The Voigt-Kampf machine of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, wheezing away as it uses iris detection technology to detect flickers of humanity in its subject, is as potent a symbol of his nightmares of the future as there is.

However stunning it is to look at Villeneuve’s sequel is unlikely to have the impact of Scott’s film. The ideas Dick propagated now seem disconcertingly familiar. Not just from fiction, but in the news, itself selected and sometimes written for us by Artificially Intelligent algorithms, edited second-by-second and displayed on tiny glowing screens: our own personal realities brought to us by corporations that know no borders.

A world in which crime is pre-detected, panicked humans rapidly turn off computers that have invented their own language, self driving cars decide who to save and drones make battlefield kill decisions without human oversight is one that Dick would have instantly recognised as his own. It was the one he had nightmares about.

But Dick didn’t have any neat solutions about how to deal with the unreal world. His heroes tend to struggle on, like Deckard at the end of Scott’s movie, heading into an uncertain future. The great visionary gave us the map, but he had no directions.

Then again, as the man said, who does?