Comparing Notes

Lillian Crawford takes us on a journey through the jazz-soaked London streets of post-War British film…

You’re walking down a street in London. You hear music coming from one of the houses. As you pass by, you look through the windows and see people dancing, drinking, smoking, kissing. The scene could come from a number of modern British films and television series, from Campbell X’s Stud Life (2012) to Steve McQueen’s Lovers Rock (2020). Rhythm brings people together to celebrate shared identities when broader society does not, and in London’s cinema, that rhythm has been around for a while; it’s there in Britain’s post-war cinema, especially the works of Basil Dearden, and it’s a beat that continues today.

It can be a lot easier to find your people in a big city like London than in rural parts. As a queer woman growing up in Kent, I didn’t find a community I belonged to until I moved out to Cambridge for university, to Manchester for my first job, and to London where I now work. I did, however, play the trombone from a young age and my love of instrumental music, from classical to jazz, helped me connect with like-minded people. Today that music might seem outmoded, especially as a means to socialise, but jazz clubs have helped me find similar people in new cities.

My attachment to jazz, rhythm and blues is attached to my love of British cinema. My cinematic education largely consisted of the most popular films made in England following World War Two: the Carry On series and the Ealing comedies. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on female post-war experience through the lens of Ealing films, and now run a blog and podcast called Listen To Lillian, which explores representations of women and queer people in British cinema. It’s important for minority groups to have a heritage, to show that we have always existed and feel that we belong.

Long before I’d spent any extended time in London, films had shown me a place where culture and diversity thrived. The most significant film director of the post-war period in this regard is Basil Dearden, who made his name at Ealing with a series of social realist films, contrasting with the comedies the studios are best remembered for today. His films held a socialist and representational agenda in a period when those aims were rare, proving extremely controversial in their day but a prospective site of identification for a 21st century audience.

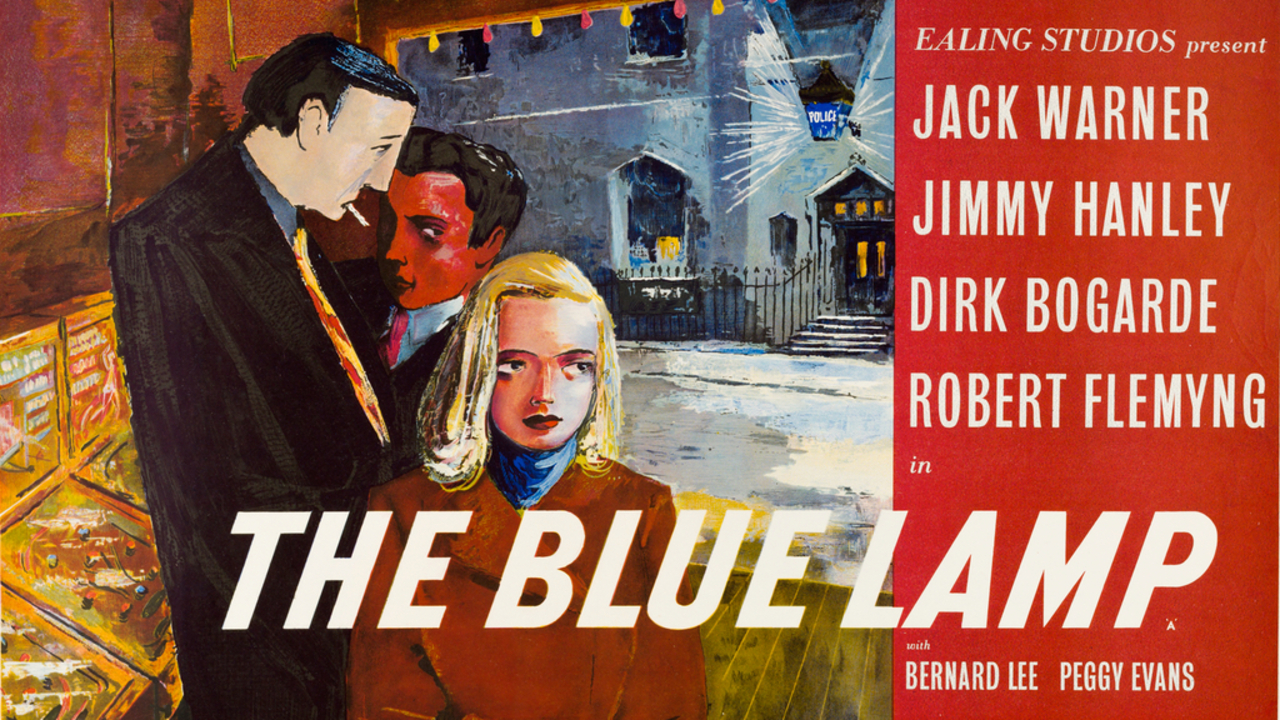

Dearden brought the techniques of Hollywood noir to the British crime film. He started with The Blue Lamp in 1950, which wove the rhythm of post-war youth culture into its fabric, translating the aesthetic of rock ’n’ roll into oblique angles and rapid-cut chases. Popular contemporary crime dramas like Line Of Duty owe their intensity to The Blue Lamp and its unflinching representation of the grittier side of the law.

Dearden developed this aesthetic with Pool Of London, radical for being the first British film to portray an interracial relationship, between black actor Earl Cameron and white actress Susan Shaw. The film’s fast montages and jazz music reflect a clash of culture forced upon the couple by racist Londoners. The film was produced as Ealing’s fortunes were declining. It had failed to meet the demands of a younger audience, and television threatened the existence of cinema altogether. Following this, as part of a strategy to recapture the success of films like Kind Hearts And Coronets or Passport To Pimlico, Dearden was forced under contract by Ealing to direct a series of comedies in the 1950s, which were a much weaker offering than his more radical dramatic work.

After Ealing was sold at the end of the 1950s, Dearden returned to pushing representational boundaries with Sapphire in 1959. The film centres on the murder of a young woman, whose partner’s family discover her West Indian heritage, and who had been passing for white. Reuniting Dearden with Earl Cameron as the woman’s brother, Sapphire is a conventional mystery drama that confronts racial prejudice head-on. The approach is less subtle than 1962’s All Night Long, which translates Othello to a party at a jazz club.

Although jazz appears in Dearden’s previous films, in All Night Long the music takes centre stage. The film opens with Richard Attenborough toasting a drink with iconic bassist Charles Mingus as the rest of the band falls in, including a dreamy line-up of saxophonists Tubby Hayes and Johnny Dankworth, as well as legendary pianist Dave Brubeck, who just happened to be in the area during filming. The plot’s never directly about race, but the attempt of a Iago-like Johnny Cousin to sabotage the marriage of Aurelius Rex (Paul Harris) and Delia Lane (Marti Stevens) simmers to boiling point at the film’s climax. Jazz can bring people together, but All Night Long shows how it can also break people apart.

At Ealing, Dearden worked with a number of gay men, including director Robert Hamer, prior to the legalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1967. Dearden’s 1961 film Victim stars several queer actors, like Dirk Bogarde and Dennis Price, in a film about the shaming of homosexuality and the impact enforced closetedness has on marriages. It was the first film to use the word “homosexual” and was banned in America.

Victim sticks out in the history of queer representation in British cinema, and certainly did when I first saw it as a teenager. Unlike Dearden’s other films, there is a lack of community, due to the fear gay people felt of the law at the time. It stands in contrast to American director Robert Aldrich’s The Killing Of Sister George (1968), which focuses on a lesbian love triangle in London. It’s particularly notable for a sequence filmed at the Gateways Club in Chelsea, making it the first film to show the interior of a lesbian venue, fit to burst with queer women dancing to live music. It’s a film that couldn’t have existed without changing social views, influenced in part by films like Victim, and how those attitudes brought about changes to the law.

Jazz in London films reached its apex in the late 1960s. Although hardly representational for the queer community or people of colour, two films set in London and released in 1966 boasted bold new jazz scores: Lewis Gilbert’s Alfie, with music by saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, scored by pianist Herbie Hancock. Although not the popular music of the day, these soundtracks broke from conventional orchestral scoring to capture the pace and bustle of youth culture and sexual revolution.

The final scene of Alfie sees Michael Caine’s bachelor addressing the camera, reflecting on his promiscuity. My nan saw it being filmed by the Thames, and was struck by the resemblance of Caine to her husband, my granddad, who just so happened to be called Alf. I picture the paternal line of my family in Lambeth, and these representations give me insight into how they lived. Their jazzy soundtracks and fast-paced rhythms have drawn me back to London – to find my own community and see where its music-filled streets take me.

This interview first appeared in Industria Studios London ‘zine available to pick up for free in London Picturehouse and Curzon Cinemas.