Ben Affleck: Older And Wiser

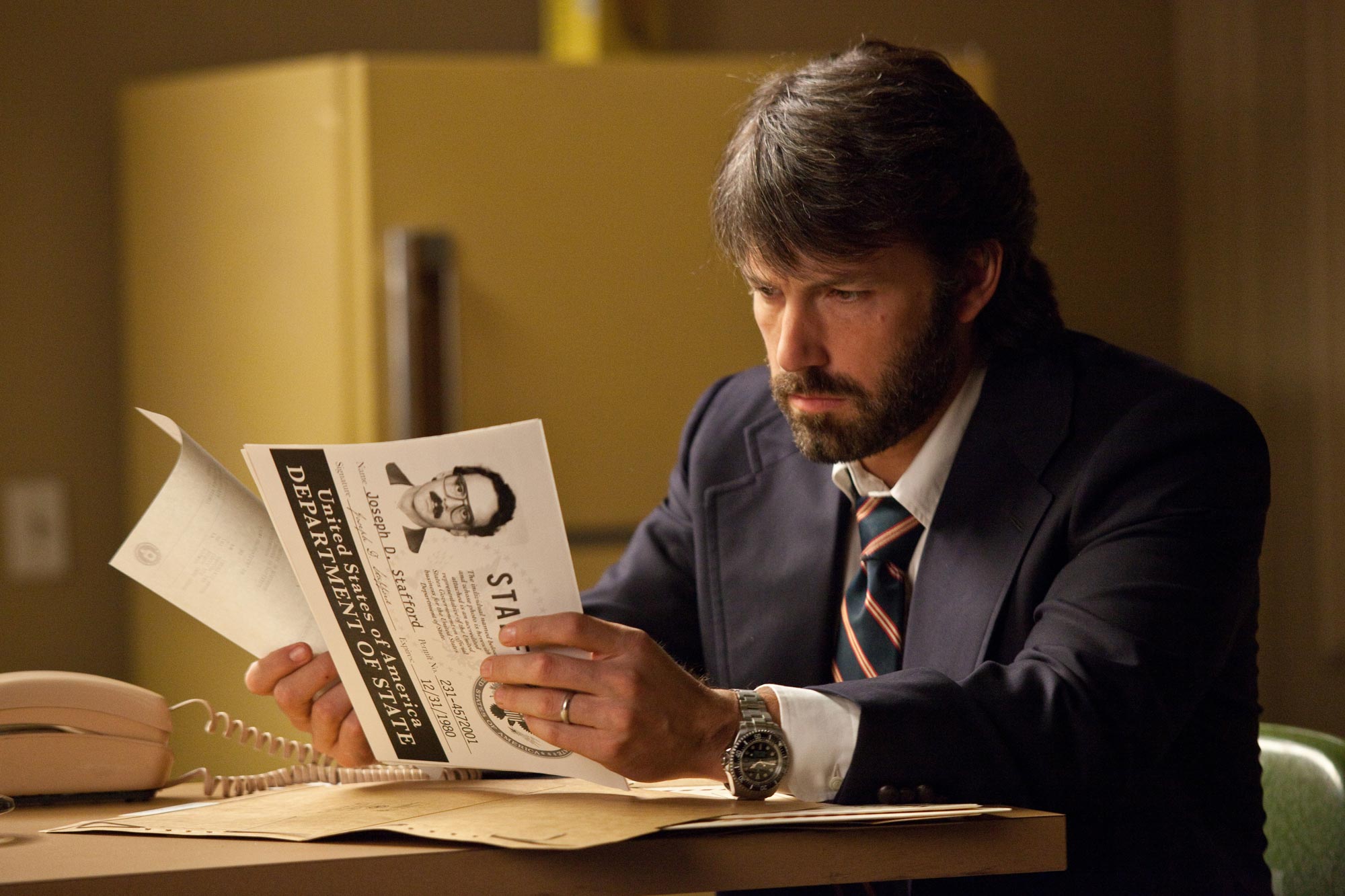

As Ben Affleck hits one of life’s milestones, he’s producing some of the best work of his career – in front and behind the camera

In many ways it’s quite hard to believe that an actor famous for such average films in the early 2000’s as Daredevil, Gigli, The Sum Of All Fears and Jersey Girl has become one of our most exciting directors. But for Ben Affleck, turning 40 has seen him producing some of the best work of his career, setting a new benchmark in grown-up, thoughtful cinema – a world away from your Jack Ryans or Matt Murdocks.

Of course we always knew he had it in him; 1997’s Oscar winning Good Will Hunting was no fluke, just that creative edge seemed to be blunted as Hollywood came knocking. In 2007 he wrote the screenplay and directed the small indie thriller Gone Baby Gone starring his brother Casey Affleck, about detectives investigating a little blonde girl’s kidnapping. The release was delayed by a year in the UK due to the similarities to the Madeline McCann disappearance, which tells you that this wasn’t a light fluffy blockbuster, but a compelling and accomplished piece for a first time director raising the bar for police procedural thrillers. Affleck followed it up with The Town in 2010, a crime drama about bank robbers in the Boston area of Charlestown – a square mile that contains more thieves than any other place in the US. His new movie – Argo – has already topped the US box office and is already being talked of as a solid Best Picture contender come February.

“Forty is apparently the new 15, so I am in my sophomore year! I don’t want to jinx anything but I feel as good if not better than I have ever felt in my life,” says Affeck. “I really like where my relationship is to my work right now, I really like the opportunities that I have had, I can work harder than I ever had, and at the same time, I have a much more rewarding home life than I have ever had. My wife is a spectacular woman! I am in a place where it is very, very good, but my psychology leads me to think, ‘Something bad must be happening. When is the other shoe going to drop?’ because I feel so blessed, so I am focused on just trying to keep things as they are.”

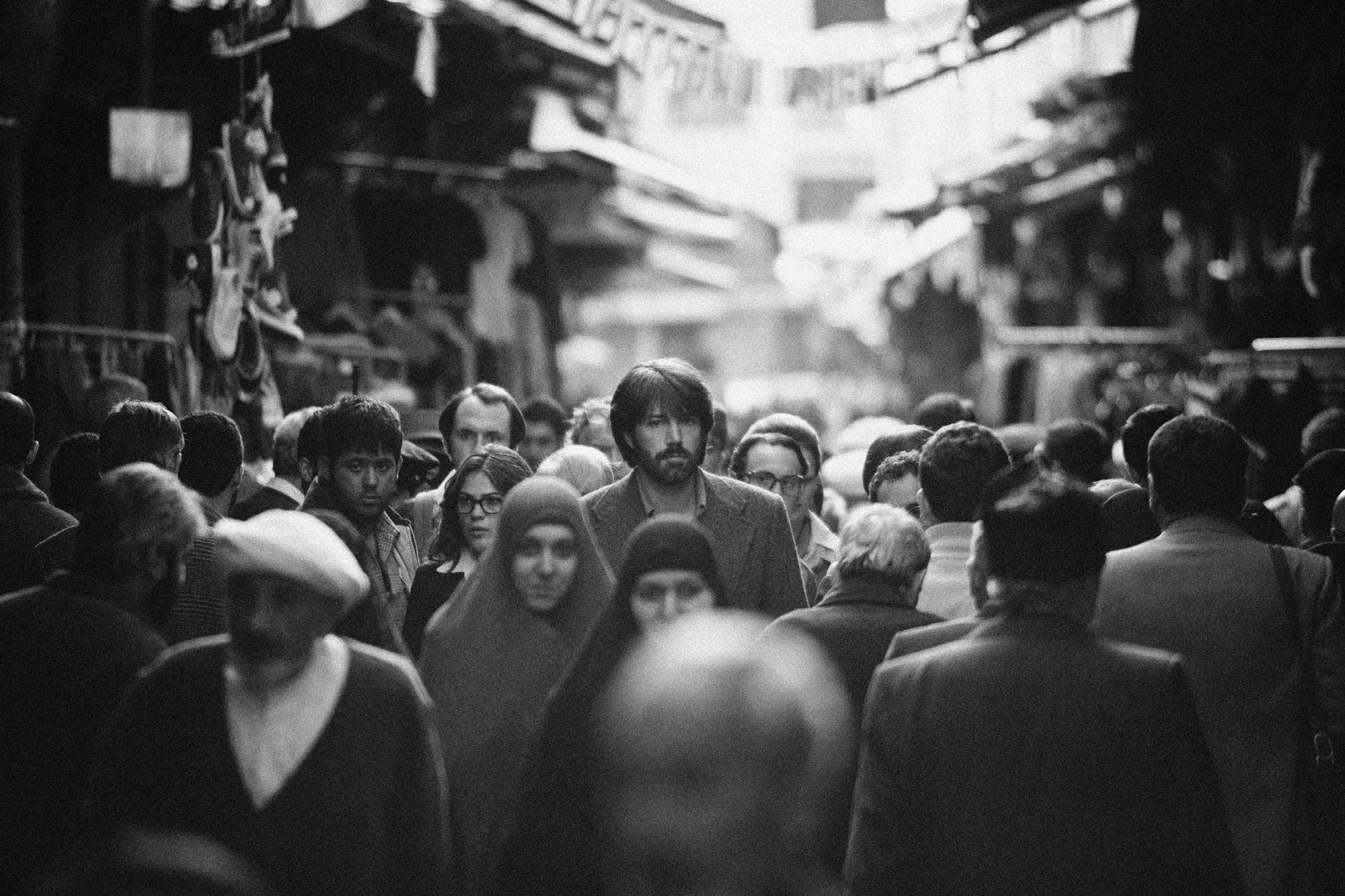

And right now he’s focused on Argo, which based on a true story, is set during the Iranian revolution in 1979 about six US Embassy workers hiding from Islamist militants in the home of the Canadian ambassador. A CIA operative Tony Mendez (Affleck) comes up with the seemingly far-fetched scheme to get them out of the country by pretending they are part of the film crew scouting Iran as a possible location to shoot a Star Wars-style sci-fi movie (Argo). It’s a story that sounds like a Naked Gun-type farce, but it’s testament to Affleck’s abilities that he keeps maintains a balance to the comedic and dramatic sides to create one of this year’s must-see films.

What was the attraction of this story?

I thought that it was a complicated drama in some ways – I really liked the idea that it was a story that was true, and that was not only informed by the events that were happening at the time but that you could communicate to the audience the complicated history that preceded that. Most Americans know a lot more about the hostage crisis than they do about the revolution in Iran that was engineered in part by the CIA and the British, and I thought we could be able to cast an interested and unexpected light on the events. But also, it was a story that was quite hopeful in a time when there is a lot to be cynical about, in terms of the West’s relationship with the Middle East. It was also one that portrayed the Iranian people as being caught in the middle rather than demagoguing this idea and making the Iranians all bad guys.

Where did you stumble upon this idea?

It was one of these things where I finished The Town and I said, “What’s the best script that you guys have there at Warner Bros. that you might be willing to let me do?” And they sent me this script that was from George Clooney and Grant Heslov, Smoke House Pictures; they had developed this story from an article and had hired a brilliant writer, called Chris Terrio, who worked on the script for several years, and they sent me the most recent draft. Unfortunately, George and Grant ended up taking it to Sony – even though Warner Bros. still had the script – so there were all kinds of attachments. Basically, I said, “This is amazing, I really want to do it,” and George and Grant were kind enough to approve me for it, and the studio let me make a movie that I thought was pretty unusual for a big studio movie.

What research did you do?

I did a ton of reading, a ton of interviewing people. I went to the State Department, I went to the CIA, I read all the people’s books. I obviously spent time with Tony Mendez and then I did a lot of researching with some of the people who were hostages – both the house-guests and the hostages in the Embassy. I was a Middle Eastern studies major in college so I didn’t need to research the history of Iran as much – I already knew about that. I wanted to go to Iran but ultimately wasn’t able to go, which was a real disappointment, mostly because I wanted to look at the physical places and get some shots of the Tehran skyline rather than having to create Tehran digitally, and shoot in Turkey.

So what was the most difficult aspect of this?

The most difficult aspect of this certainly as a director, was that it has several different tones, and I was concerned that the movie still feels real and be able to work comedically in the middle where it has the Hollywood sequence. The beginning with the embassy takeover, a terrorist act, then you have the All The President’s Men Washington vibe, then you have this comic 70s Hollywood thing with Alan Arkin and John Goodman – who’s are both hysterical – then you have to jump back into the very real story about these people hiding out, and how they eventually escaped. I was very concerned about juggling that stuff. So we created different film stocks to try to navigate that, I was terrified that one of these elements might corrupt another, and tone is one of those things that if you get it wrong while you are shooting, you can’t fix it later. It’s just dead. Other than that, it was just physically a lot of work, trying to act and direct.

Why couldn’t you go to Iran?

I wasn’t turned down by the Iranians, but I tried to go when I was researching a different movie, but the State department said, “Listen, we don’t recommend this.” The second time, I was just like, “You know what, I’m just going to go anyway, instead of asking for permission,” because there are flights in and out and I’m going to try to get a Visa and it’s possible. Then the advice I got was, “This could actually become a distraction for your movie.” The people I talked to talked about going to visit places and then the Government officials would turn up and want to take pictures and then it would be this whole thing, and you might be seen as endorsing political figures there. Basically, I would be unwittingly drawn into the political situation of Iran and that was not what I wanted to do. I just wanted to be an artist telling a story. If I did do that and it did end up getting publicity, it could actually prevent me from making the movie. Everything I ever heard about Iran is that the Iranian people are great and wonderful people who want to have fun and want to be part of the world, but who are living under a repressive, dictatorial regime which oppresses people, ironically in a way not unlike the Shah did. They just veil it in Islamic fundamentalism. Ultimately, it’s a few people at the top holding all the power, making all the decisions, with a titular parliament that can’t really do anything, so it’s a repressive political system backed by violence.

How much did you actually deviate from the facts?

We tried to stay really close to what happened. In fact, that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to use that photo montage at the end of the movie to try to impress upon the audience as they were walking out – hopefully before they walked out – that they had just watched a story that was basically complete fact, and here are the real people, in real life, and here are the real places where this happened.

How did you enjoy the hair, beard and wardrobe?

I enjoyed the wardrobe more than the hairstyle. That got to be very hot. I was thinking, “How did the Bee Gees perform all those years without getting heatstroke?” The hair and the beard were a bit of ordeal. Walking around in real life with that hairstyle and beard, I got the odd sideways glance. It was fun to do something different. What I didn’t want to do was one of those things that you make a big thing out of it being the 70s, so like everybody’s got big choppers and platform heels and bell-bottoms. I wanted the period to feel real but recede into the background. Like if I took a photograph of us all sitting around right now, and in 15 years showed it to somebody, you would go, “I don’t know when that was? 2005? Or 2012?” It could be either. And that’s what I wanted for this, for the 70s. You don’t just want cars from ’77-79, you use cars going back to the ‘50s and ‘60s, because those were the cars that were still around. I was more interested in making it feel real than there was to point to a specific style or trend in that way.

Why did you go into Middle Eastern studies?

I am going to date myself a little bit because I went to college in 1990, I didn’t want to do theatre or film or anything like that, I could learn about drama elsewhere – I thought the educated actor or director was a better actor or director or writer. I liked foreign policy and I liked politics, and the field that was really popular was Soviet or Russian studies – that was where all the Government jobs wanted you to have studied and it was hot and current and was what was happening in the world, and the Middle East was a very backwater department; it didn’t have many people in it and it wasn’t seen as being very relevant to the United States, and I had to keep doing independent studies with professors to make up new classes. I thought it was this incredibly mysterious, exotic, fascinating place, and I saw it as opaque and it made me want to penetrate that opacity and to find out what is at the root of this mystery, this conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis; and this strange land in Saudi Arabia where there is nothing but desert and Bedouins for hundreds of years, but then suddenly you have gleaming skyscrapers. The whole thing seemed very exotic and interesting to me, so I signed up.

Have you done much travelling there?

Yeah, I’ve been there. I’ve been all over. I went travelling earlier and I’ve travelled later, ironically, to spend time with our troops there. So I’ve been in the Middle East, I’ve been in Kuwait and all the Gulf countries, and Turkey – if that counts – Jordan, Egypt, everywhere in North Africa, Libya. Yeah, I’ve travelled all over. I love to travel and it’s a fascinating place. You find things that you didn’t at all expect when you travel there – sometimes good, sometimes bad.

Is there a movie to be made out of the whole Syrian situation?

I almost went to Damascus three years ago because I read an article in the New York Times which said, “You know, you can really just go to Damascus, it’s beautiful, it has great hotels,” and I thought, “I have to do this.” But I didn’t. And now, obviously, it’s radically changed. I think there will be endless books written about it and I definitely think a movie. I think that people collectively sense that the end of this story is yet to be told. Ironically, there was an article in one of the major American newspapers today about the CIA giving weapons to Syrian resistance groups and it conjured up in my mind this whole idea of once again we are getting involved with a country, we pick a side and we hope we are doing the right thing but it’s a powder keg and one can never be certain of its outcome.

How is it directing yourself?

I don’t really practically direct myself. No one is talking to you when the cameras are actually rolling so you are on your own anyway whether there’s a director or not. So I do for myself what I would like another director to do for me which is to give me a lot of latitude, to allow me to do a number of takes, to try a bunch of different things, and when I have done all that, I go back over to the monitor and look at it, and either it’s disastrous or it’s workable. Where I do the directing is in the editing room. You pull a bunch of footage back into the editing room and I’m so critical of myself that it’s easy. I’m just like, “Take this out, take that out, that that out – it’s horrible!” I find one line, one moment that I like and am like, “Oh good, let’s put that in the good bin.” I find the more that you are critical of your movie, the easier it is to make because you can just get rid of so much stuff.

You seem to have a great affinity with the movies of the 70s, both as an influence on you as a director and as a fan.

I think that was the golden era of movies. Certainly there were great movies before that, and since, but that’s the era that I respond to. Most of my movies have used models from that era. For this movie, Missing was an inspiration, for some of the Iran-feeling stuff. All The President’s Men was something that I used for the interior CIA stuff. I wanted it to feel un-slick, a non-action hero movie of it, just a bunch of guys sitting around smoking cigarettes, typing out forms, where women were just the secretaries and there were very few African-Americans, just so I could say, “This is an honest portrayal of life at that time. Unflinchingly,” and allow the audience to reflect on that. For the Hollywood stuff, I used a (John) Cassavetes movie called The Killing Of A Chinese Bookie, which has a great Californian, late 70s feel to it. It’s got lots of zooms in it, and the zooms go with these moves and it’s got punchier colours, so I used that for a lot of the 70s stuff, putting the zooms in, playing scenes out really wide and flat for periods of them. The Verdict is a movie I’ve looked at both for my first movie and for this movie, the moral ambiguity in it, the broken protagonist. Also, in The Verdict, you have that older character to Paul Newman – and their relationship, like mine to Bryan Cranston’s, was complicated, and there was love there but there was a lot of rocks grinding against one another. I also thought my hair and beard had a Kurt Russell, 1981 thing.

Or Serpico?

Serpico, yes! A little bit like Serpico. I was just looking at (Sidney) Lumet’s resume the other day and it’s amazing. Nobody else did that range of movies, and did that many brilliant movies. Starting with Twelve Angry Men and basically ending up with Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, and all the stuff in between, just massively talented, and amazing movies, and very much rooted in that feel of the 70s which was all about character and writing, and allowing that to be at the forefront and trusting that to tell the story. He is somebody I definitely look to.

Does it make you think about how much better it was back then, without cellphones and Facebook?

It’s getting harder and harder to make a movie with any tension in it, because nowadays you just go, “He would just message her on Facebook,” or, “He would Tweet it!” You would just pick up your cellphone and it would be impossible to get around all the ways we have to communicate with each other. And there is something nostalgic about that time, when if you left your house, people just couldn’t get hold of you. They might call and someone would say, “He’s out, I don’t know where he is, so call him when he gets back.” If you needed to call someone, you found a payphone. You didn’t know if someone was trying to reach you. It was like it was more free. Doing a period movie, I noticed how much more tightly we have wound ourselves to one another. In some ways, it is good, but in some ways, I am like, “Do we really wanted to be tied this closely to one another, all the time?” But that’s a different movie?

Are you worried that there is not really room for a movie like this in a landscape filled with The Avengers and Twilight?

Yeah, I don’t know what my expectations are for this movie, but they are certainly modest. I don’t think anybody imagines that this is going to be a gigantic box office success story. It’s got a number of elements that historically have been challenging: one, it’s a drama. Dramas have a harder time performing than other movies. Two, it takes place in the Middle East, which has been off-putting in movies in the past, even if you look at a great movie which won an Oscar like, The Hurt Locker, that still didn’t really do very much business, despite great direction, great acting, the whole thing. It’s also a period movie, so that’s three things… those movies don’t do as well. But this movie doesn’t have to be Transformers to be successful. We kept the costs fairly modest so that we weren’t responsible for having to get back a galactic amount of money. I think there are places for different kinds of movies. I think there is a market place for a movie like this, and for giant tent-pole movies. Naturally, it’s concerning, but I think at the heart of it, it’s both a true story and also inspiring.

Did you use a lot of special effects in Argo?

I felt like I was making one of these superhero movies or something because I had so many effects, except my effects were really boring – taking signage down, taking satellite dishes off walls – because once you get into looking at all the things that change in a place between 30 years ago and now, it’s neverending. Plus we had to change the Turkish to Farsi, and everywhere we shot in America, we had to take out all the… one of the enduring legacies of 9/11 is that every public building has these barricades and huge cement blocks outside, so we had to take that stuff out. It’s pretty boring, but that took many weeks.

Those times you want to go to Syria or Iran, does your wife say, “Oh great, I want to come,” or does she say, “Can’t we go to Cabo instead?”

My wife would just love to travel, but having three children in a row has meant that I have got to travel more than she has, so she wants to travel so much that I think at this point, she would happily come along to Tehran, but she may prefer Cabo.

So the worst thing is having to watch a lot of Disney movies?

I have a long life ahead of me of watching princess movies.

You haven’t had a $100million movie since Daredevil, which was 2003. Was that decision made for you, or did you make that decision? Were you bored of all that tabloid crap and just wanted to step back?

First of all, The Town made $92million, so that is very close to $100million, and internationally it crossed $100million, so I will take exception to that statement but only in that regard. The rest of what you said is definitely true: I spent a lot of time on a certain type of treadmill chasing a certain type of movie, trying to keep up a certain type of pace, but it got to a point where in some measure the choice was made for me which was that I was going to step off for a little bit, take a break – I wanted to direct so I wanted to focus on directing. I wanted to continue acting but in the way that I did in Hollywoodland or State Of Play, or movies where I wasn’t necessarily out in front as the lead, so I could do more interesting things that were a little more below the radar, and then I felt ready to act and direct with The Town. It was a refocusing. And I have a very different life than I used to have, and I much prefer the life I have now. I do things that I am much more interested in now, and I think I am a more mature now. I don’t chase an idea of what my life should be. I try to think what I would like my life to be and I think about the ways that I can get there. And yeah, I definitely made some movies that didn’t work – that’s for sure. I wish I hadn’t, but I certainly wouldn’t give that back if it meant I didn’t end up where I am now.

What do you like doing when you are not working?

I have found that what happens is I had all these hobbies and stuff, and that all went away when I had kids. When I am not working, I am home and I am watching princess movies or I am playing games. I am not trying to learn the guitar like I was before. I have a couple of guitars in my house that are just gathering dust, they haven’t been touched since my first child was born. So mostly I am running around with the family. I also do travel, I do some work with the Eastern Congo Initiative in West Africa and I make way for that, because that’s part of my life and I give it some bandwidth, so really there is nothing else left except for my family, which is wonderful.

You mentioned your influences from the ‘70s, but what modern directors or actors inspire you?

There are some amazing directors working now: (Alejandro González) Iñárritu is incredible – I look at all of his movies before I direct something and try to steal everything I possibly can. This time, I stole his DP! Paul Thomas Anderson is my favourite guy directing now, I think he has got a brilliance where you just go, “Not only would I never have thought of that, it’s outside any world of thinking that I would have had.” I know him a little bit so I try to steal from him too, but he is so distinctive that he is hard to steal from, it would be such obvious theft, like a dye-pack exploding in your hand. I think Spike Jonze is really good. I think Terry Malick is one of my favourites – sometimes I understand it, sometimes I don’t but I really like watching the movies, and I like him a lot. There are just so many: the Coen Brothers are some of the great geniuses of cinema now. As far as actors: Sean Penn – what he did in Milk was one of the great feats of acting, ever; Phillip (Seymour) Hoffman is an amazing actor, and I think Matt (Damon) is a really great actor. I think my brother is a really great actor. I also Joaquin Phoenix is a really great actor. Obviously, Scorsese is incredible and still making great movies after so long in this business. Benicio Del Toro is a great actor. Daniel Day Lewis may be the best – if he’s not the best, he is tied. There are some movies in which I would be terrible to direct and there are movies that I would be really right for. This was a movie in which I was really interested in the subject matter before I even came to it, so I was definitely better suited to this than I would be to something else. And as an actor, I am better suited to some things and poorly suited to others. I don’t know. It’s hard to say. I have been acting for a long time and directing is more recent, and also writing, and I view them as all part of the same discipline: you write, you act, and that’s part of the whole thing of directing. When I was in theatre class in high school, when I was with Matt, my brother and a lot of really good, interesting and talented people, we would improvise as actors,